A Texas Standard special

From a 1923 service station to the world's biggest Buc-ee's: A brief history of gas stations in Texas

By Michael Marks

Flashy logos, customer giveaways and attendants are memories of a bygone era as stations have evolved over the past century.

The gas station as we know it today appeared in the 1910s. Before that, if you needed gas, you’d go to a grocery or a hardware store, where you’d pay a guy with a bucket to pour some into your Model-T.

Once pumps were invented, then came the service station, where you could drive in, gas up, and get back on the road fast. They started in big cities, then spread to smaller ones. But there still weren’t any between Fort Worth and El Paso in 1923, the year that Fred and Edith Wemple moved to Midland to open the first.

“It was dusty; none of the streets were paved; all the streets were dirt,” Edith said during a 1978 interview with her grandson, Cliff Avery. “And the road from here to Odessa, the sand was so deep that you’d bog down.”

The Wemples had a good life in East Texas before moving to Midland. They lived in Marshall, where Fred worked for the railroad. They could have stayed and been happy. But these automobiles presented new financial opportunities – so they went west with $500, bought a property in Midland and built the Ever-Ready Auto Service Station.

Edith kept the books; Fred took care of the customers – which in those days meant doing routine maintenance, along with a fill-up.

“You had to clean the windshield, and you had to put water in the radiator, and you had to check the oil,” Edith said. “And stand there and hold that old nozzle most of the time putting the gasoline in; they didn’t have the one that you just put in, walk off and leave.”

The Ever-Ready was an independent service station. But in Texas, there were plenty of companies that both drilled for oil and sold gas directly to customers, including Magnolia, Humble, and Esso – one of the predecessors to Exxon.

Fred and Edith Wemple’s sons, Allen and Ted, pose with employees’ children for an advertisement for the Ever-Ready Auto Service Station. Photo courtesy Cliff Avery

Fred and Edith Wemple’s sons, Allen and Ted, pose with employees’ children for an advertisement for the Ever-Ready Auto Service Station. Photo courtesy Cliff Avery

The Wemples got into the business during a transformative time for American gas stations. More than 100,000 new stations went up between 1920 and 1930: mostly simple, boxy buildings.

But after World War II, that changed. Roads improved, and cars became cheaper and more reliable. Strange new forms and bright logos began to appear on the sides of highways. Gas stations sprouted arches, awnings, towers and turrets – anything to stand out. Some were paneled in ceramic or glass, or roofed with Spanish tile. Logos like Mobil’s red Pegasus, Texaco’s star-T and the Sinclair dinosaur cast a neon glow across the freeways of America.

“When you were driving down a road, you would often want to go to something that was familiar to you,” said Dwayne Jones, author of A Field Guide to Texas Gas Stations. “Long before you got there, you would see the form of this building, and then the signage that goes with it.”

There were gimmicks to build loyalty, too. Texaco introduced the “Registered Restroom” program, a seal of approval to assure travelers they could always find a clean bathroom. There were giveaways – everything from maps to drinking glasses to wrapping paper.

The industry’s next big shift came in 1973, when other oil-producing nations stopped selling to the U.S. Drivers faced long lines and high prices for gas.

Stations profited at first. But as the industry grew cautious, they cut costs. Giveaways disappeared, and so did a lot of stations. Abandoned pumps became a standard sight across America. As a young man, Michael Witzel spent a lot of his time photographing them.

“You’d have crumbling architecture and, you know, peeling paint on the gas pumps,” said Witzel, an engineer and travel historian. “To me they looked like sort of artistic artifacts from the past, antiqued by the weather; each one had sort of a different patina over the years.”

Many of the abandoned stations were destroyed, or picked over for memorabilia. Some were turned into something else.

The idea of the service station more or less disappeared by the ‘80s. New stations had similar designs, and logos on signage got smaller to make room for the price per gallon.

“You don’t have memories of being there when they’re giving away things, or the attendant pumping the gas, that kind of thing,” Witzel said. “It’s all self-service and convenience marts.”

As for the future of gas stations, it might be just off Interstate 10 in Luling.

In November, I went to the groundbreaking of what will be the world’s biggest convenience store. It’s a Buc-ee’s, the Texas gas station chain known for its big stores, beaver mascot and selection of snacks. This new one will be over 75,000 square feet once it’s finished – enormous, but not out of line with other Buc-ee’s locations.

WhisperToMe, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

WhisperToMe, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Local dignitaries celebrated at the Luling groundbreaking with someone in a beaver costume, and the company’s president, Arch “Beaver” Aplin.

“This one … will give us some real opportunities to do a better job merchandising,” Aplin said. “We’ll have a better food selection, more parking spaces, more fueling pumps, everything.”

Buc-ee’s changed the gas station game with this model of more. There are still fewer than 60 Buc-ee’s locations nationwide – miniscule, compared with the thousands of Exxons and Chevrons. But Buc-ee’s is growing and attracting imitators – though Aplin said that’s not on his mind.

“I don’t spend much time thinking about that,” Aplin said. “We’re just kinda trying to do our thing, and if that changes the industry, so be it.”

Changes over the years

Cities Service Company

- Began in 1910 in Oklahoma as a utility company

- Had stations throughout most of Texas by 1950s

- Rebranded to Citgo in 1965

- Now based in Houston, owned by Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A.

Humble Oil and Refining Co.

- Founded in 1911 in Humble, Texas

- Purchased by Standard Oil in 1959

- “Happy Motoring” signs were a staple of stations and ads

- Brand existed until 1973, when it became part of Exxon

Magnolia Petroleum Company

- Named for one of its founders’ aunts, Magnolia Willis Sealy

- Existed from 1898 to 1959, when Magnolia was folded into the Mobil brand

- ExxonMobil still uses Magnolia’s red Pegasus logo

- Built stations with Spanish architectural influences in the 1930s

Texaco

- Began as The Texas Company in 1902 after the Spindletop oil discovery near Beaumont

- Founders included Jim Hogg, 20th governor of Texas

- Rebranded to Texaco in 1959

- Purchased by Chevron in 2001

In sprawling Texas, cars are king. How did we get here – and where does public transit fit in?

By Alexandra Hart

It would take a major shift in priorities to design cities in a way that wouldn’t rely on personal vehicles. But some progress is being made.

Gas stations exist because cars exist.

And not only do cars exist – they’re nearly a requirement in a state as vast as Texas. Whether you’re commuting to work or traversing the state on a road trip, there aren’t many options besides getting behind the wheel – at least, none that match the ease, speed and convenience of driving yourself.

Some people love driving. I am not one of them. I wondered why we ended up like this, and if a less car-dependent Texas was even possible.

I was first curious about what it’s like to live without a car in cities. So, I asked Reddit’s Texas forum. What I learned was: people have really strong feelings on the matter.

The thing is: It’s possible. It just isn’t easy. And for people who can’t afford a vehicle or are living with disabilities that prevent them from driving, it’s the only option.

Valerie Mitchell has been carless in Austin for almost a decade. One day her vehicle broke down, and she couldn’t keep up with the cost of repairs or afford to replace it.

“There was a lot of stress and anxiety that went into owning a car,” she said. “I just didn't want to deal with it.”

She got rid of the car and has been taking the bus ever since. Even though she’s in a better place financially, she hasn’t replaced the vehicle – and doesn’t plan to. She said it’s cheaper and less stressful, but it’s also been limiting in other ways: She has to be picky about housing, looking for places on north-south bus routes.

“I realized that the east-west buses don't run very often, and they don't run late, either,” she said. “They run until like 9:30 or 10:30. So you're kind of stuck on the east side if you are out there long enough.”

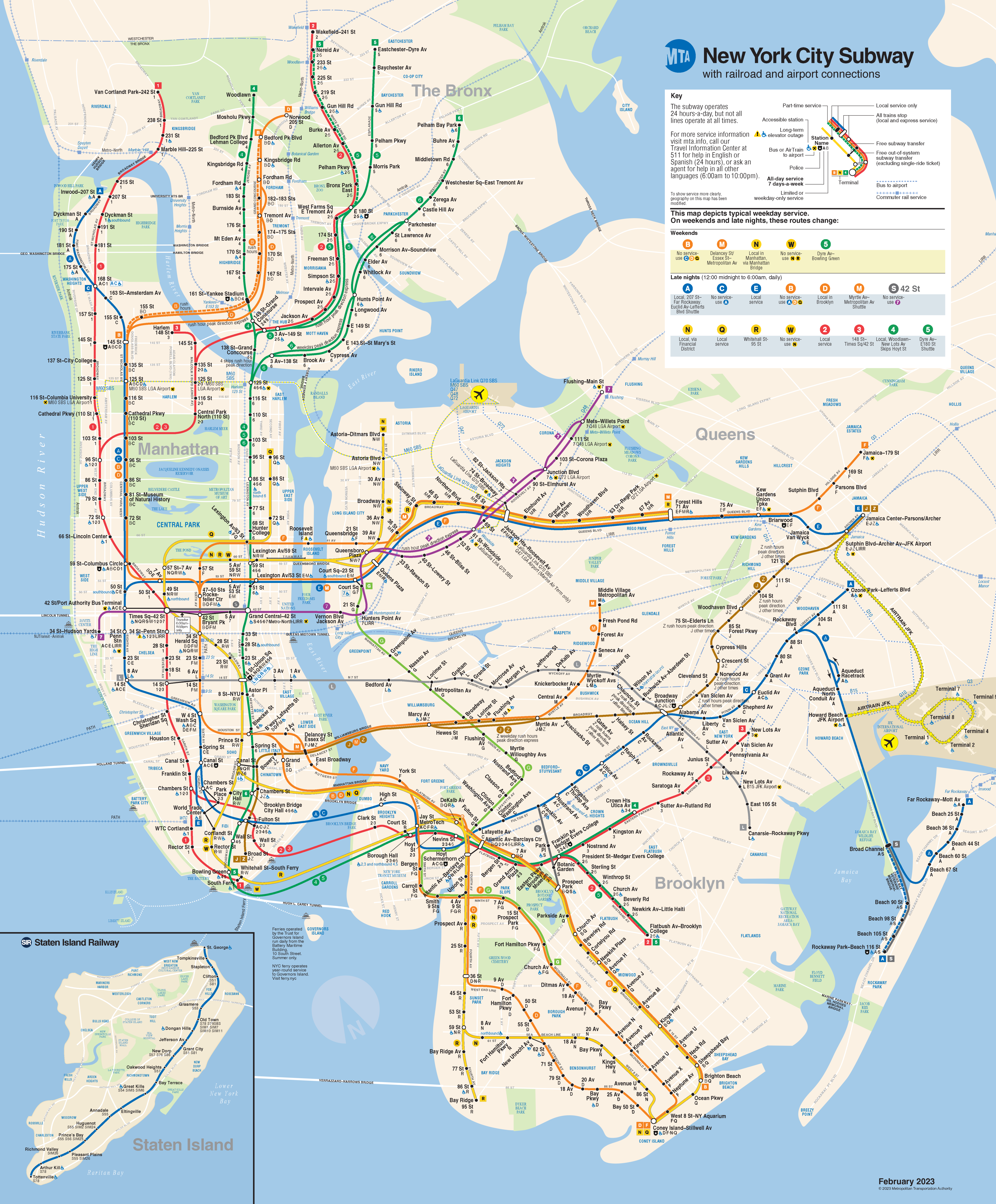

Surely it doesn’t have to be like this, right? I mean, look at the mass transit systems in New York, Boston and Chicago. Why can’t we have that?

Metropolitan Transportation Authority

Metropolitan Transportation Authority

I asked Alex Karner, an associate professor of Community and Regional Planning at UT-Austin.

“New York is really an outlier in terms of U.S. cities,” he said. “New York developed largely before the automobile came on the scene, and other cities across the country did not have the kind of same luxury; they were much less densely populated prior to the advent of [the] automobile. There were fewer people living in them.”

Timing is a big factor. Cities that grew rapidly, long before cars became commonplace, ended up denser and more walkable. And for much of Texas’ history, it was a very rural state.

Still – Houston, Dallas and San Antonio were developing as urban centers way before cars were the norm. There were other ways to get around. But nowadays? People willingly living without cars in these places are the exception, not the rule.

The rise of suburban sprawl

So, what happened?

First: Cities in general became pretty gross around the turn of the century – think pollution, crime, horse manure in the street. People understandably wanted out. Streetcar suburbs became a thing, but if you live in one of these places – like Hyde Park in Austin – you’ll notice those trolley routes are long gone. Karner said those once-thriving systems became plagued with problems like corruption and poor labor conditions.

“Public opinion kind of turned,” he said. “There was a lot of mismanagement that led to the decline of these streetcar systems in the early 20th century. And at the same time, the automobile was coming on the scene.”

As car sales took off, so did funding for car infrastructure like highways and gas stations.

And if poor conditions in cities plus the rise of the automobile were the spark that lit the fire of suburban sprawl, the civil rights movement poured gasoline on it. Karner said the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling to integrate schools was a major flashpoint.

“White folks did not want to abide by the spirit of Brown vs. Board,” Karner said. “So that led them to leave central city areas, leave some of those closer-in suburbs and move further out where they could establish white communities with white school districts.”

By then we also had the interstate highway system. With personal vehicles and efficient highway systems, wealthy suburbanites had no reason to increase funding for transit. In fact, many actively fought against it.

“You can look back at the historical record and see the arguments that people were making at the time, and they were explicitly racial arguments,” Karner said.

Bus systems remained in cities but weren’t a high priority. We ended up with large, spread-out cities that rely heavily on personal vehicles. It’s hard to break out of the cycle of car dependence because the way we approach traffic encourages sprawl.

“Roadways become congested, and then we try to identify which links are congested,” Karner said. “We expand them, which reduces travel times, but that actually makes it more attractive to travel further. So then people move further out.”

Investments in transit projects

If all these people must have a car for commuting, they’re going to rely on that as their primary mode of transportation instead of taking a less-convenient bus. Then there’s less interest – and therefore less funding – to develop a better bus system.

It would take a major shift in priorities – and a lot of money – to design Texas cities in a way that would make walking, busing or biking more appealing than driving. In the meantime, some groups want to make it easier for people to drive less, even if that doesn’t mean totally abandoning cars.

One of those is Ghisallo Cycling Initiative, a biking nonprofit that operates in Austin and San Antonio. Executive Director Kari Kuwamura said that step one to getting more people on bikes is helping them overcome fear.

“People think it's not safe to be out on the road, or they think it's unsafe to be by themselves,” they said. “Or, you know, ‘what if something happens to my bike?’”

The group focuses on programs to teach bike safety and maintenance and helps people plan routes for their bike commutes. But that can only do so much when it comes to dealing with bike-unfriendly infrastructure. Kuwamura said San Antonio has been making strides in recent years, investing more in transit alternatives.

“The most recent bond cycle there, you know, adding extensively to the Greenway. But also they're investing the most money ever into Via,” San Antonio’s public transit system, they said. “You're also a cyclist if the last mile or two of your commute is, you know, getting from the bus to your work.”

They also said that building trust within communities that would benefit most from improved infrastructure is crucial to winning support for these projects. That includes cities embracing anti-displacement policies that prevent people from getting priced out of their homes.

“Folks are scared that their taxes are going to go up, or that that area of town is going to get gentrified and they're going to get pushed out,” Kuwamura said. “I think protecting those communities and letting them know that they deserve that nice infrastructure and they're not going to get kicked out – I think that’s a really important piece that the city needs to pay attention to.”

Other Texas cities are investing in mobility projects, too. Austin has its Project Connect initiative. Houston’s METRO system was just granted $5 million in federal funds to improve commuter bus routes. Dallas Area Rapid Transit is giving $111 million to member cities to improve areas around transit stops.

The Capital Metro Downtown Station adjacent to the Austin Convention Center celebrated its grand opening in October 2020. Gabriel C. Pérez / Texas Standard

The Capital Metro Downtown Station adjacent to the Austin Convention Center celebrated its grand opening in October 2020. Gabriel C. Pérez / Texas Standard

But the truth is: Personal vehicle ownership is never going away completely – and maybe that shouldn’t be the goal. Cars are part of our national identity.

“I think there is still a deep American kind of … I don't want to say ‘love affair’ with the automobile. But there is, right? People love to drive. They love the freedom that it affords,” Karner said.

But what if people also had the freedom to get around just as easily – and safely – without a car? Maybe more people would get on board with driving less and find some of the same advantages that Valerie Mitchell did.

“I just realized how stress-free it is,” she said. “Also, walking is good for you, and it makes me feel good as exercise. I still have a driver’s license; I’ll drive if I have to. I just do not want a car anymore.”

And advocates say if and when cities do invest more in public transit, they need to get input from people who rely on it most – not just the potential users they want to attract. Because, car or no car, everyone deserves to be able to get where they need to go.

GET MORE NEWS FROM AROUND THE STATE:

Tacos and tamales: Austin-based gas station chain sells fresh food with the community in mind

By Sarah Asch

JD’s Market has 15 locations in the Austin area, and each comes equipped with a full kitchen.

If you walk in the doors of the JD’s Market at the Mobil gas station on Austin’s Riverside Drive – say, on a Wednesday – you will smell fresh mole bubbling.

To the right you’ll find traditional gas station fare. But on the left is a full kitchen and taco bar, plus glass cases showing off stacks of pastries and sweet bread.

Ismael Tónico makes these baked goods daily. This includes pan dulce, Mexican rice pudding, decorated cakes, cheesecake and dipped strawberries with different flavors and toppings.

There isn’t much in the way of seating, just one table and a row of stools. But there are always customers picking up food.

The wall in front of the kitchen is painted to look like faded yellow stucco, with “fresh from the oven” painted in looping letters. The rest of the room is painted in different colors: pale purple over the milk, sky blue over the frozen section, deep red above the wine.

Customers can pick up fresh pastries, including conchas, donuts and churros, from the display case at JD’s Market in Austin. Sarah Asch / Texas Standard

Customers can pick up fresh pastries, including conchas, donuts and churros, from the display case at JD’s Market in Austin. Sarah Asch / Texas Standard

If you keep following your nose, you’ll find Maria Levya, who’s worked as a cook at JD's for the past five years. She says there are daily specials, like enchiladas or beef stew; on Wednesdays, it's always mole.

“We make the mole with red chiles. You put it to brown there [on the stove], you put this in the mole cups, you add all the seasonings,” she said. “Then you add the chicken legs.”

Levya helps with everything in the kitchen at the gas station. She said she keeps her nails long – over an inch and painted blue with decorative gems; they’re her real nails, not press-ons – so she can flip tortillas and bread on the grill without burning her fingers.

There are 15 JD’s gas station locations in the Austin area. Wendy Rincón, who leads the marketing department, said that although the family who owns the chain is from the Middle East, the company did research and found the Latino population in East Austin was underserved.

“All this was created based on a study of the needs in the City of Austin when it came to gas stations,” she said.

Rincón said JD’s wants to offer fresh, hot food with a menu that reflects the community. Some locations have gone beyond Mexican food to include dishes from Nicaragua and El Salvador on the menu, she said.

Back in the kitchen, Levya said the dough for tamales here at the gas station is similar to what her grandmother taught her to make when she was 10 years old growing up in Mexico.

Maria Levya makes pork tamales in the kitchen of JD’s Market. She’s worked there for years and said the dough is similar to what her grandmother taught her to make as a kid in Mexico. Sarah Asch / Texas Standard

Maria Levya makes pork tamales in the kitchen of JD’s Market. She’s worked there for years and said the dough is similar to what her grandmother taught her to make as a kid in Mexico. Sarah Asch / Texas Standard

Levya said customers regularly drive from towns a county over for JD’s tamales, but the menudo – a traditional Mexican stew with beef broth and hominy – is even more popular, with some people coming in from two hours away to buy it.

Pedro Razo Hernández, who lives near the gas station, is a big fan of the menudo and stops by for food at least twice a week.

“I really like the menudo; it’s very flavorful,” he said. “The beef broth and the veggies: onion, cilantro, a little serrano chile. It’s really good.”

Razo Hernández is one of the many faces that Adelaida Flores, who’s worked at the JD’s Market on Riverside for years, has grown used to seeing.

“Some have moved but still visit the store,” she said. “They come for the tamales, for the tacos, for everything. And on the weekends they come for the menudo.”

What's the key to running a successful gas station? Tyler store owner has a few tips

By Sean Saldana

Mahi Food Mart owner Daniel Shaikh has focused on location, a clean store and regularly updating his inventory to meet the needs of his community.

Outside the Mahi Food Mart in Tyler, Daniel Shaikh recently revealed something ironic about owning and operating a gas station.

The gas itself “is more of a loss item to attract customers in,” he said.

Despite selling around 600 gallons of gas every day, fuel sales are a part of his business where, even in the best-case scenario, Shaikh is breaking even.

“And that's if you don't count if somebody drove off with my nozzle,” he added.

The National Association of Convenience Stores (NACS), a trade association representing gas stations and convenience stores, estimates that for every gallon of gas sold at the pump, store owners net around 10-15 cents. If a gas station owner is in a competitive market or is looking to pull more customers into their parking lot, that number is even lower.

At Mahi Food Mart, Shaikh purchases the gas himself for $2.86. He sells it for $2.89 – a markup of only three cents – and then has to tack on a 3% credit card fee.

For gas station owners, all the money is made inside.

Want to turn a profit? Focus on the location

Originally from Pakistan, Shaikh and his family arrived in East Texas in 2009. In less than a decade in the industry, the family made the transition from gas station workers to gas station owners.

“In 14 years, I've basically got my hand on the nerve so I can tell exactly what day, what sales are going to be and, you know, how much profit I'm getting,” Shaikh said.

One of the things that’s made his family’s entrepreneurial journey successful has been a focus on location – the biggest factor potential owners consider when deciding whether to open a business.

Jeff Lenard, vice president of industry advocacy for NACS, said that “in the olden days, it was pretty simple: You'd stand by the side of the road with a clicker, and you'd count for a couple hours. It is way more sophisticated now.”

Today, entrepreneurs look at everything from census data to daily traffic patterns to figure out where to put their stores.

Among the questions that Lenard said potential owners need to answer before opening a store are:

All of this is why Shaikh and his family decided not to open a store in Carthage – a town of about 6,000 where they had been running a store for seven years – but in Tyler, a city of more than 100,000.

Since its opening in 2019, and especially since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, Shaikh has seen a much wider variety of people pull into his store.

“We have noticed that a lot of people move here from out of state: California, Washington, Maryland, you know, bigger states,” he noted.

After running a gas station in Carthage for years, Daniel Shaikh and his family opted to move to the larger city of Tyler to open their own. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

After running a gas station in Carthage for years, Daniel Shaikh and his family opted to move to the larger city of Tyler to open their own. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

Tidying up

Getting customers in the store is half the battle. Once they’re in the building, small business owners like Shaikh need to keep them comfortable enough to spend some money.

“Most convenience store customers are going in to address something that they need now,” Lenard said. “They're hungry. They're thirsty. They need to use the restroom."

A great way to make sure potential customers are comfortable: keep things clean. The average customer doesn't want to be greeted by sticky countertops or mysterious odors.

“About 20% of customers say they use the restroom when they come into a store. So that's usually where you start,” Lenard said. “Make sure that's clean. Make sure that everything when you walk out is presentable, and then they start their shopping experience.”

Shaikh put it more simply: “You have to have a very clean bathroom, a very clean kitchen and very clean beverage counter. Those three things, if they're dirty, you're losing customers.”

Knowing the community

When Shaikh first purchased his gas station, it was a corporate-run store – one with fixed sets of products and services, a static design and “not very individualized,” he said.

After purchasing the business, Shaikh and his family started informally surveying customers: “We started asking people, ‘Hey, what do you need? What you like?’ From cigarettes to beer to soda.”

Meeting the needs of Tylerites is an ongoing process, one that requires constantly analyzing the subtle ways in which people’s preferences are changing.

Shaikh shared one of his methods for making inventory decisions: “We have customers that come in, ‘Hey, this product is great.’ And I'll snap a picture and I'll send it to my sales rep and see who carries this product, which distributor has it. Is there demand in my area? Are people asking for it?”

When asked if there are any Tyler-specific products that have become popular in recent years, Shaikh pointed to Karma, a low-calorie flavored water.

“Gatorade was too sugary, and water wasn't sweet enough,” he said. Karma “pushes them to drink more water. In their mind, they're doing their part of drinking water – a more fun way of it.”

The product has been such a hit in Tyler, Shaikh has gone from offering three flavors to nine flavors in his beverage section.

Mahi Food Mart owner Daniel Shaikh says Karma flavored water has taken off with customers, so he’s now stocking more flavors. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

Mahi Food Mart owner Daniel Shaikh says Karma flavored water has taken off with customers, so he’s now stocking more flavors. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

Branching out

In 2018, Shaikh was skeptical about disposable vapes, unsure about the future of e-cigarettes. But as somebody who’s always looking to try out new products, he purchased one display and placed it on his front counter.

Within two days, he completely sold out. Then he bought a second display. Then a third.

“My vape sale was matching my store sale for the whole day,” Shaikh said.

Vape sales were eventually so strong, Shaikh made the decision to open his very own smoke shop – right next door to his gas station, in a storefront that used to be part of a rundown dry cleaner’s.

Now, it’s Mahi Smoke Shop. It’s also been a massive boost to his business.

Daniel Shaikh opened the Mahi Smoke Shop next door to his Mahi Food Mart in Tyler. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

Daniel Shaikh opened the Mahi Smoke Shop next door to his Mahi Food Mart in Tyler. Sean Saldana / Texas Standard

“This is what pays the bills,” Shaikh said while motioning around the gas station. Then, pointing toward the smoke shop: “That’s where we’re making the money.”

Over the next few years, Shaikh is planning on adding a kitchen, upgrading the gas pumps and repaving the parking lot. Removing and relocating fuel storage tanks from underground – something he needs to do before adding the kitchen – is estimated to cost him $240,000.

Even in the face of a looming recession, Shaikh continues to make large investments in his business.

“My dad came in with $500 in his pocket, and that even that was borrowed. And now I'm up where I own my gas station and vape stores and stuff like that,” he said. “So if you work hard, even in a bad economy, you can do something with it.”

Test your knowledge of gas prices

By Laura Rice

Let’s answer all the questions you’ve ever had – and some you never knew you had – about gas prices.

Play the quiz below – or by clicking here – to test your knowledge, and check out the answers courtesy of Daniel Armbruster of AAA Texas public affairs.

'All I want to do is drive': Meet the truck drivers who keep the supply chain running

By Kristen Cabrera

These truckers are defying stereotypes while balancing their love of the road with their love of family.

Off northbound Interstate 35, heading into Jarrell, Texas, Kellylynn McLaughlin geeks out over the sound of several different semitruck engines.

“So this is a KW – it’s a Kenworth – but listen to him,” she says over the whirling buzz of the engine. “I mean, like, this guy’s made for power.”

The differences are subtle: The sound of the KW she points out has a really strong fan; the international truck next to it has a distinct pattern – da-duh da-duh da-duh. It’s easy to see she loves the sound of these trucks.

Kellylynn McLaughlin at the Flying J outside of Austin. Kristen Cabrera / Texas Standard

Kellylynn McLaughlin at the Flying J outside of Austin. Kristen Cabrera / Texas Standard

Born in Lubbock – the daughter of an amateur race car driver – McLaughlin grew up around fast cars and loud motors. And in middle age she finally answered the call of a diesel engine as a career path.

“I started when I was 50 just to see if I could do it,” she said. “And then I found out I was actually loving it. And there was a lot more to learn. And then I became good at it.”

McLaughlin – warm, bright and bubbly, with trendy strands of iridescent tinsel in her blonde wavy hair – is not at all how truck drivers are stereotypically portrayed.

Truckers in the media tend to be gruff, scary loners. Just look at Large Marge from the 1985 cult hit “Pee-wee’s Big Adventure.” Her face transforms into a Tim Burton claymation nightmare, scaring many children for life.

McLaughlin said truck drivers have a bad rap, “but it's completely wrong. We're an incredibly diverse group of people. We come from all different backgrounds, languages, cultures, ages.”

But the mystery around truckers was once admired, said Anne Balay, author of “Semi Queer: Inside the World of Gay, Trans, and Black Truck Drivers.”

“So there used to be a way that truckers were seen as independent rebel bad boys, but it was appealing,” she said. “You know, it's sort of the cowboy myth.”

But as the pay went down over the years, Balay said, perceptions changed.

However, if you grew up in a truck driving family, like Tony Bergara, your thoughts on truckers were vastly different.

“I'm not out there to be mean,” he said. “I'm out there making a living, and I mean, I'm going to have fun. My dad told me when I was young, ‘If you enjoy what you do, you would never work a day in your life.’ And I enjoy what I do.”

Bergara’s a seasoned driver. It’s in his blood: His father, grandfather, uncles and brothers all drove trucks.

After driving all over the U.S., he can best any GPS for directions, even if he’s been somewhere just once before. And his colleagues often call him for advice on the best truck stops for rest or good places to eat. Bergara loves the open road, but he knows it's not for the faint of heart – especially if you have family.

“I'm not going to lie. I still get homesick,” he said. “After 43 years, I still get homesick. It’s hard.”

Truck driver Tony Bergara shows off a detailed miniature of his truck. Kristen Cabrera / Texas Standard

Truck driver Tony Bergara shows off a detailed miniature of his truck. Kristen Cabrera / Texas Standard

Mark Herrera, a 22-year-old from Edcouch-Elsa in the Rio Grande Valley, is about to start a family. As a migrant worker he was able to take advantage of a grant program that paid for his commercial driver’s license classes.

“Coming from the Valley, you see things that you don’t really see in the Valley – I see mountains; I see woods and all of that,” he says. “That’s what I like, personally.”

And now that Herrera and his high school sweetheart are expecting a baby, the job has gotten a bit more complicated.

“As a truck driver all I want to do is just drive and make some money, save some money,” he says. “It’s also bad because I'm not gonna be there for my girlfriend when she's sick or whatever throughout the pregnancy.”

It’s a trade-off that both Bergara and McLaughlin had to navigate, too. Bergara drove locally until his kids turned 18, then got back on the road. McLaughlin's children were teenagers by the time she started, but not everyone was 100% okay with her decision to drive a truck.

“For me, it was challenging because I didn't get a lot of support from family and friends for this career because of typical stereotypes,” she said.

But that didn’t stop her. Giving up wasn’t an option: “It just felt like I needed to do it.”

It’s almost like a call to duty. And while driver shortages continue to plague the industry, those like Herrera, Bergara and McLaughlin are putting it all on the line.

Postcards from around the state:

Snapshots from three Texas gas stations

Corpus Christi: Ben's Community Market

Tragedy strikes a family, but now their convenience store is a base from which they can keep giving back to the community.

By Raul Alonzo

Photos by Raul Alonzo

San Antonio: Valero

Sweet family memories of free drinks and quality time after Spurs victories in the NBA Championships.

By Jackie Ibarra

Photos courtesy of Jackie Ibarra and Pixabay

Valero photo: Derrich, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Spurs photo: photo taken by flickr user michael248, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Highway 71: Hruska's

Kolaches from this roadside bakery eased pre-college jitters – and became a tradition.

By Glorie Martinez

Photos by Glorie Martinez

Road photo by Michael Minasi

When cars run on batteries, not gas, where will we go for a fill-up?

By Shelly Brisbin

It takes a lot longer to charge an electric vehicle than it does to fill your gas tank – and the future likely holds more charging options, and more ways to occupy your time while you wait.

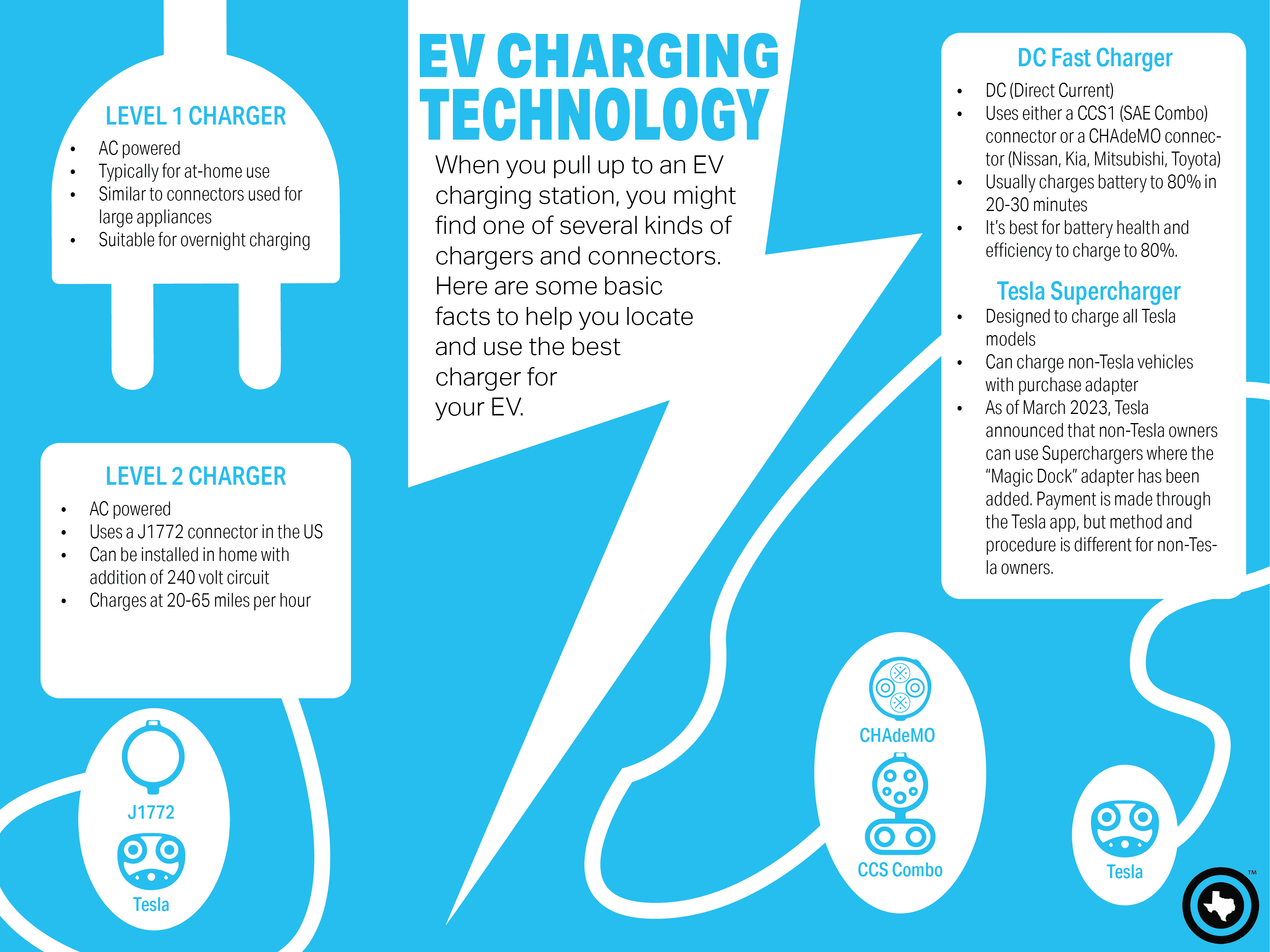

If you've ever considered buying an electric car, or EV, your thoughts probably revolve around power – how to get it, where to get it, how often to get it. And you might expect EV charging to center around the familiar gas station setup: Pull up, connect your car to a power source, pay and be on your way quickly.

But in a world where a vehicle’s power comes from the electric grid and a battery, rather than a tank, where you get fueled up in the EV future could look a lot different than the gas station of today. And though most current EV owners do most of their charging at home, the need for access to charging on the road has car makers, retailers, government agencies and gas station owners planning and building the infrastructure we’ll all need as more of us choose EVs.

“Today with an internal combustion vehicle, you have to go to a gas station. That's actually the only place you can get fuel,” said Sam Abuelsamid, principal analyst at market intelligence firm Guidehouse Insights. ”But in the future, a lot of people will be getting their energy at home. But there will also be public charging at facilities that look very much like gas stations do today. Or perhaps maybe a better analogy would be something that looks more like a Buc-ee’s.”

Buc-ee's, with its many locations along major highways and large-scale retail and food offerings, is the kind of place people can easily spend an extended period of time when they stop to refuel. That’s important because it can take 20-30 minutes to charge an EV, even with today’s fast chargers.

Illustration by Raul Alonzo / Texas Standard

Illustration by Raul Alonzo / Texas Standard

Abuelsamid said EV drivers will be drawn to places they can hang out for a while and have a meal or a cup of coffee, or do some shopping, while they wait for a charge. And that’s the kind of experience retailers who don’t currently sell gas will want to provide their EV customers as well.

Level 2 chargers, which charge EVs much more slowly than fast chargers, are far less expensive for businesses to install. So they’re also available at many locations and will continue to be a part of the public charging mix. Experts believe many EV owners will use this option when they don’t need a full charge but want to use time they’re already spending in a parking lot to charge their battery.

Shelly Brisbin / Texas Standard

Shelly Brisbin / Texas Standard

“I think we're going to see a lot of 'why not plug in while I'm here?' behavior. But when they need electricity fast, I think that's when you're going to see them going more towards the traditional convenience gas retailer who's going to have those DC fast chargers to get them back on the road quickly,” said John Eichberger, executive director of the Fuels Institute, a research group funded by the transportation energy industry. He said the desire to plug in whenever possible is a symptom of the range anxiety – the fear that you won’t be able to reach a charger in time when you need it – that keeps some from considering EVs in the first place.

“I still think that even as we get comfortable with it and then we'll trust our at-home charging or our twice-a-week recharge at a public facility or an apartment complex, I still think that if there's a charger available, ‘why not top off?’” Eichberger said.

But beyond range anxiety, having plenty of charger location options and types is essential for drivers who can’t charge at home. If they don't have access to a garage or off-street parking, these drivers won’t have the ability to install a charger of their own. Car makers are investing in charging infrastructure, partially as a way to broaden EVs’ appeal in the used car and budget market segments: Tesla operates its own superchargers, and GM and network operator EVgo have partnered to install 2,700 fast chargers across the country.

“What GM and EVgo are looking at is places like grocery stores where you go on a regular basis,” Abuelsamid said. “So you're not going out of your way to charge your car. And you're going to be there for at least 20 or 30 minutes.”

Nick Allen waits for his Tesla to fully charge with Davide Bonatti at a Supercharger Station in Austin. Jessie Curneal / Texas Standard

Nick Allen waits for his Tesla to fully charge with Davide Bonatti at a Supercharger Station in Austin. Jessie Curneal / Texas Standard

The need to support EV charging is likely to impact businesses like Buc-ee's, or a gas station that includes a convenience store.

“Even with a traditional gas station-type facility, I think what we'll see is a transition to those facilities putting in a little more space for their convenience stores or an onsite restaurant or whatever,” Abuelsamid said.

That’s already true in Texas.

“I would say, in the last 18 months or so, we see major convenience store chains, conventional retailers getting into EV charging in a really major way,” said Lori Clark, a program manager on the air quality team at the North Central Texas Council of Governments. “Where they're looking at themselves as fueling stations, not gas stations.”

Clark’s agency is the regional planning organization for the 12-county Dallas-Fort Worth area. It figures prominently in how North Texas will spend its portion of the $407 million in EV charger funds the state will receive under the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law passed in 2021.

The first phase of infrastructure money will fund EV fast chargers on major corridors – mostly interstate highways – with the goal of ensuring stations with at least four chargers each are available every 50 miles. Clark said most of the money goes to public entities, with 20% available for public-private partnerships. All charging stations must be publicly accessible, and there's an uptime requirement, too. The buildout is supposed to be completed by 2027.

Credits

"Pumped: Food, fuel, and the future of Texas" was reported and produced by Michael Marks, Alexandra Hart, Sarah Asch, Sean Saldana, Kristen Cabrera, Jackie Ibarra, Glorie Martinez, Raul Alonzo and Shelly Brisbin.

Production help from Marissa Greene and Erik Acosta.

Managing editor Gabrielle Muñoz, digital producer Raul Alonzo, and social media editor Wells Dunbar put together the digital presentation.

Our showrunners and editors were Laura Rice and Matt Largey.

Texas Standard's director is Leah Scarpelli. Our technical director is Casey Cheek, and our executive producer is Rhonda Fanning.

Our host is David Brown.